It’s Still Legible, and It’s Not Racist: Notes towards a History of the City Seal of Worcester, Massachusetts

No Council this week; here’s an essay

Reprinted from the March 2025 issue of Happiness Pony.

Heart of the Commonwealth—A name applied to Worcester on account of its central location in the state. The origin of the term is uncertain, but it was used as early as 1820, then generally in reference to the County rather than the Town. The City Seal has the device of a heart, which tells its story without any Latin.

—Franklin Pierce Rice, Dictionary of Worcester (Massachusetts) and Its Vicinity (1889)

Our city seal is beautiful, and its origins are shrouded in mystery. We’ve spent a lot of time looking into it, and had a lot of help from the Library, the Museum, and the Clerk’s office, and we still can’t figure out who created the final design. Here’s what we’ve learned, followed by speculation. Perhaps you will be the one to find the final piece of this puzzle.

1847: Worcester didn’t have a seal until it became a city. In 1848 it surpassed the 12,000 residents that the state required for incorporation as a city, which would grant it the power to elect a Mayor and City Council and stop having town meetings.

November 8, 1847: Alderman John Milton Earle (abolitionist, retailer, and Worcester Spy publisher) moved that the town should petition to become a city.

February 28, 1848: The Massachusetts House of Representatives approved the petition.

February 29, 1848: The State Senate and Governor concurred.

March 18, 1848: The town voted on the matter, with two-thirds of the 1,513 men gathered at Town Hall approving the deal. Worcester’s government now had a mayor who was the chief executive (unlike the current setup), and a bicameral legislature sometimes, confusingly, called the City Council: a 9-person Board of Aldermen (which included the mayor, who chaired it), and a 24-member Common Council who were elected from various districts of the city.

April 24, 1848: Henry J. Howland petitions “to be appointed City Printer.” This is tabled. A couple days later, Lincoln & Hickox ask to be City Printer. The Council creates a Joint Special Committee on Printing.

July 31, 1848: Howland petitions to publish the city ordinances in his City Directory, and later offers to throw in 200 copies of just the ordinances for the low price of $50. Eventually, the city takes him up on it.

Henry Jenkins Howland was a notable printer and the uncle of the legendary Valentine Card mogul Esther Allen Howland. Henry’s parents were Southworth Allen Howland Sr., who married Esther Allen (no relation). They had a number of children, including Henry’s brother Southworth Allen Howland Jr., who married a different Esther Allen (no relation). Among their children were Southworth Allen Howland III and Esther Allen Howland, who it could be argued was also a III.

November 27, 1848: It’s proposed to the Board of Aldermen that they and the Common Council create a committee to establish a city seal. On December 18, the Aldermen approve this. On January 8, the Common Council approves this. Aldermen Stephen Salisbury II and Isaac Davis, and Councilors Benj. F. Heywood, Adolphus Morse, and Freeman Upham begin their work.

January 22, 1849: The Committee presents their proposal: “The Seal of the City shall be of a circular form, having in the center as a device, the figure of a heart, with a motto over it, in these words, ‘With Heart and Hand,” and having on the margin, beginning at the center of the left side, the words, ‘Worcester A Town June 14, 1722. A City Feb. 29, 1848,’ according to the design hereto annexed.”

February 5, 1849: The Aldermen discuss the proposed seal, and Alderman Benj. F. Thomas (hereafter known to me as “the only Alderman with taste”) asks for the motto to be removed. Everyone else votes for the seal as-is, and the proposal is sent to the Common Council. The local newspapers, who usually ignore municipal politics completely, cover this minor controversy.1

February 19, 1849: The Common Council, perhaps noticing that the motto is “With Heart and Hand,” and there’s a heart but no hand on the seal, vote for “a hand with an open palm” to be added, and send it back to the Aldermen. Both bodies seemed to be meeting at the same time, because the Aldermen immediately voted for the non-hand seal and sent the proposal back to the Common Council, who immediately voted for the hand again and sent the proposal back to the Aldermen, who tabled it.

March 30, 1849: A Friday, the final day of the political year. Monday will be inauguration day. The Aldermen propose a Committee of Conference to resolve the conflict over the seal, the Common Council agrees, and the committee is formed with Aldermen Salisbury and James Estabrook, and Councilors Morse, William T. Merrifield, and Horace Chenery. The committee proposes to end the controversy by removing the motto, and everyone agrees. “The Seal of the City shall be of a circular form, having in the centre as a device, the figure of a heart, and having in the margin, beginning at the center of the left side, the words ‘Worcester a Town, June 14, 1722, a City, Feb. 29, 1848,’ according to the design hereto annexed.”

This is a really stripped-down design. The name of the city, a heart, a couple factoids. Note that ᴡᴏʀᴄᴇꜱᴛᴇʀ begins at the 9 o’clock position, in both the language of the ordinance and the sketch submitted to the City Council.

April 11, 1849: Brand-new mayor Henry Chapin2 is asked to procure a seal, and pay for it out of the Contingent Expenses account.

Sometime before December 31, 1849: Henry J. Howland publishes The Worcester Almanac, Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1850, Including the City Ordinances. The image of the seal in the Almanac is the seal as we know it today.

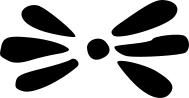

Which is to say, not the design proposed to the City Council. Now ᴡᴏʀᴄᴇꜱᴛᴇʀ is centered at the top, rather than beginning on the left side, and a laurel3 wreath is added. An ungainly, sadly sparse seal has been transformed into a beautiful swan. It’s still simple, but now there are a dozen small, beautiful details, like the starbursts separating the clauses, or the tiny “ʏ” in FEBY, or the subtly dotted inner circle, or the contrasting textures of the heart and laurels.

1867: The city ordinances are revised, and the seal ordinance now describes4 the one used for the past 18 years: “The seal of the City of Worcester shall be of circular form, having in its centre the figure of a heart, encircled with a wreath, and in the margin the words ‘Worcester a Town, June 14, 1722; a City, February 29, 1848.’”

We don’t have any examples of city paperwork stamped with the seal in 1849, so we don’t know what the seal ordered by the mayor’s office looked like. We don’t know if Howland’s Almanac reprinted that seal or reinvented it. And, to get to the heart of the matter, we don’t know who designed it.

Speculation: We can imagine that Henry Howland, who was already contracted to publish the ordinances, was contacted by the mayor’s office to make a seal. He had one of his engravers or another subcontractor clean up the design. Centering ᴡᴏʀᴄᴇꜱᴛᴇʀ is easy. Adding the wreath, open at the top and tied with a ribbon at the bottom—its thickest point—counterbalances the shape of the heart and fills dead space in the seal. It’s a good choice, and an obvious one. Laurel wreaths appear frequently as “supporters” in heraldry and other official designs, have symbolized “honor” for a long time, and were part of the seal of many American polities, including Plymouth Colony (1629), New Amsterdam (1654), and Boston (1823). Combining a heart with a wreath isn’t unheard of, but it’s pretty uncommon—the only official use of this design I found was the back of this coin celebrating Queen Anne in 1702 (with the wreath half-oak, half-laurel).

How could such a haphazard process have led to such a strong symbol? When the seal was eventually rendered in color, the red heart and green wreath were a great combo. And, like a martini, the seal has just enough parts to not be minimalist, but no more. It’s been redesigned time and time again, and it’s always recognizable. If you walked around the city for a few hours, you might spot redesigns from several eras, without realizing you weren’t seeing exactly the same design. (Earlier this month I spotted half a dozen versions around Worcester Common alone.)

Nowadays, many polities are redesigning old seals and flags to remove offensive elements and have something that works in a variety of contexts. I’d call a lot of these designs “minimalist.” Worcester got it right from the beginning, and while every generation is going to want to give it a refresh, it’s never required a real redesign. After all these years and countless revisions, it’s still legible, and it’s not racist.

(Written and researched by Mike Benedetti, with, as always, additional writing and research by Jen Burt and Ali Reid.)

Clerk’s minutes from Board of Aldermen meeting, July 31, 1848: “License to exhibit a live seal, was granted without charge.”

The Daily Spy

Wednesday, February 7, 1849

CITY AFFAIRS

[...] The report of the Committee on the subject of a City Seal was accepted. The shield is to bear a heart, with the motto “With Heart and Hand.” Around the circumference is to be the words “Worcester: a town in 1722 — a city in 1848.” A motion to strike out the motto, as inappropriate to the device, was negatived — the mover only voting in the affirmative. The device of a heart and hand, with the above motto is not new, being, if we mistake not, the seal of one of our eastern counties, as well as one of the London Clubs or Trade Unions. But the motto with the heart alone, as a device, certainly strikes us as rather incongruous. Indeed, it reminded us of the Alderman who undertook to play the “lapsus linguae” joke, and, for that purpose, procured a leg of mutton. We had hoped that for our city seal we should have something original and appropriate, both as to the device and motto—something suggested by the history of the place, or connected with its prosperity and growth. The Heart as indicating our local position is not, perhaps, objectionable as a device, with a suitable and appropriate motto, such for instance as, “Its pulsations give Life,” or either of many others which might be suggested. But, we must confess, that if the order adopting the report of the Committee should be adopted by both boards, we should not anticipate any particular pleasure from listening to the criticisms which might be bestowed upon the seal of the City of Worcester.

Worcester Palladium

February 14, 1849

SEAL OF WORCESTER

Our city officials, as we learn from the Spy, have fixed upon a seal for the corporation.

“The shield is to bear a heart with the motto, ‘With Heart and Hand.’ Around the circumference, is to be the words, ‘Worcester, a town in 1722 — a city in 1848.’”

The Spy takes exception to the proposed seal. Of course, on a matter of such tremendous importance, everybody is expected to have some suggestion to make. Ours is that a fruit cart in the street, with a tall man peeping over into it, would be a device that would suit some folks. It would look natural.

After being asked to order the city seal, the second most interesting thing that happened to Mayor Henry Chapin during his time in office was May 3, 1850, when his office (downtown at the corner of Main and Sudbury) was bombed by (allegedly) some pro-slavery hoodlums (one a lawyer/journalist/postmaster/counterfeiter, the other a machinist/bowling saloon owner).

We asked a consulting botanist to identify the plant that makes up the wreath in the drawing, and we were told it doesn’t particularly resemble bay laurel, or oak, that it’s more just a plant-like object.

Since Worcester’s seal didn’t match the one described in the ordinances for the first 18 years it was a city, I hope you will start a sovereign-citizen-type movement that believes the current government of Worcester is illegitimate and so you don’t have to pay your property taxes or shovel your walk or something.

A very delightful read, great history!

Mike -

This was a wonderful bit of history. Also glad to see that Happiness Pony continues to ride.